One of the strongest pillars of modern finance, and modern portfolio theory as taught to MBA students everywhere, is the belief that “return is directly correlated to risk.”

The argument is that, in order to get higher investment returns, you must always take on higher levels of risk. To put it another way: For an investor to earn better returns than average, they have to buy riskier assets than average.

According to accepted dogma, in other words, risky stocks deliver higher returns as a function of being riskier. The extra risk requires compensation for rational investors to accept it, and higher returns are the payoff for doing so.

So far, so good. Except a new research study shows the theory to be wrong.

In the stock market, higher returns are not always correlated to higher risk stocks. In fact, the opposite may be true; over long periods of time, low-risk stocks show better returns than high-risk stocks.

This research, if further confirmed, could shake the pillars of modern finance. It takes one of the most bedrock assumptions and turns it on its head.

The findings are in a paper titled “The Volatility Effect Revisited,” by David Blitz, Pim van Vliet, and Guido Baltussen of Robeco, a Dutch investment firm with hundreds of billions in assets. In addition to his quant role at Robeco, Baltussen is also a professor of finance at Erasmus University.

“High-risk stocks do not have higher returns than low-risk stocks in all major stock markets,” the paper confirms. “Volatility appears to be the main driver of the anomaly,” they add, with a high degree of persistence across time and markets.

“From a practical perspective,” the authors go on to say, “we argue that low-risk investing requires little turnover, that volatilities are more important than correlations… and that other factors can be efficiently integrated into a low-risk strategy.”

The researchers looked at a 55-year period of equity performance from 1963 to 2018, comparing the beta-adjusted returns of different stock portfolios. They more or less found that, over the full 55-year period, “high-beta” stocks had a worse risk-adjusted return than low-beta ones.

Beta is a historical measure of stock volatility in relation to the broad market. So if a stock has a beta of 2.0, that means it is twice as volatile as the broad market (as determined by a benchmark like the S&P 500). If a stock has a beta of 0.5, it is historically half as volatile as the market, and so on.

If these findings hold up, they could also be a nail in the coffin for the efficient market hypothesis (EMH).

That is because, if EMH is correct, market prices always reflect rational behavior. But there is no rational reason for low-volatility stocks to show better returns than high-volatility stocks, over a period of 55 years.

If a stock has lower volatility, that is a positive feature, all other things being equal. Lower volatility stocks are like domesticated pets versus wild animals. Their behavior falls in a more predictable range, and they generally let investors sleep better at night.

If a stock has high volatility, in contrast, that is a drawback. High-volatility stocks are harder to manage. They can exhibit wild behavior and create large swings in portfolio value. They can be tough on your stomach lining.

If lower beta stocks show better returns, that would suggest investors who buy high-beta stocks are behaving irrationally on average, which would mean markets are not efficient. After all, why would anyone pay a cost (in the form of higher volatility) in order to get less?

There is another view of how markets behave that fits with the study’s findings. If you take the starting point that markets are not efficient, that investors are often emotional, and that investors are sometimes greedy or hasty and make mistakes, the mystery is explained.

High-beta stocks, which have higher volatility, tend to be “story stocks” with the potential for big rewards. These stocks are exciting, and some of them have huge potential.

After all, if you can find the next Amazon or Visa or Domino’s Pizza in its early growth days, you could see returns in the thousands of percent. This is true and will continue to be true.

As a result of this, investors tend to “chase” high-beta stocks in search of that life-changing upside. The trouble is that, while a handful of stocks actually deliver on their potential, the majority of high-beta stocks are duds. They don’t live up to the hype. That means the extra volatility is a cost and a risk, but doesn’t deliver the implied reward.

Low-beta stocks, meanwhile, tend to be not as exciting. They more or less trundle along, with fewer investors “chasing” them in pursuit of a big return.

This makes it easier for low-beta stocks, as a group, to outperform their high-beta brethren over the longer term. In the low-beta group, there is less performance pressure, and more potential for “steady as she goes” type trend returns. In the high-beta group, in contrast, the weak performance of the duds drags down the strong performance of the stars.

In some ways, this new study simply confirms what we already knew: Risk and return are not automatically correlated. If you are smart and rational, you can find ways to earn superior returns with less risk.

This is true because markets are not efficient, and investors are emotion-driven beings — which creates the opportunity to benefit via smarter decision-making.

The study also further justifies our wariness when it comes to high-beta, high-volatility stocks. Can it be worth it to own a high-volatility asset? Yes, absolutely. But there has to be strong justification for it.

All things being equal, higher volatility really is a cost (in comparison to lower volatility). That extra cost can be worth paying if the opportunity is so clear, the investing or trading idea so strong, that the extra cost is obviously worth it. If you’re confident you have a winner on your hands, a position makes sense.

But these strong conviction conditions should only hold for a selective handful of high-volatility names. The vast majority of them will not pass the test. This is why, on average, investors do worse with high-beta stocks as a group. They aren’t selective enough.

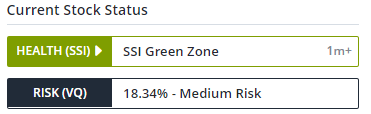

With TradeStops, you can easily determine the average volatility of a stock. Below is a screenshot example for Apple (AAPL) showing both the Stock State Indicator (SSI) and risk rating, or Volatility Quotient (VQ).

|

TradeStops lets you determine at a glance whether a stock is low, medium, high, or sky-high risk, as based on our proprietary volatility measure.

And now you can benefit from the knowledge that, for more than half a century, low volatility stocks have been the more logical bet on average, delivering better returns as a group than high volatility ones.

That means it makes sense to default towards lower volatility stocks by default — unless there is a strong, situation-specific reason to do otherwise.