Zillow (Z) used to be a real estate portal that made its money from advertising. More than 180 million users would visit the Zillow site or mobile app each month, and real estate agents would pay Zillow to have their services displayed alongside home listings.

Now Zillow is in the home-flipping business, which requires huge amounts of capital and puts it in direct competition with its advertising base (real estate agents). Is this new business model brilliant or crazy?

One person who thinks it’s a terrible idea is Steve Eisman, a legendary money manager who features in the book-turned-movie “The Big Short.”

Eisman famously led a hedge fund team that earned more than $1 billion in profits from the subprime mortgage crisis. Prior to the housing bust, Eisman’s teams shorted instruments known as collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. They increased their position size aggressively after deep-dive research convinced them the banks were sitting on highly leveraged piles of financial toxic waste — and they turned out to be 100% right.

Now, Eisman says Zillow is his largest short position.

“What I find ironic about it is, why do people love internet platform companies? They love them because they generate a lot of revenue, they generate a lot of free cash flow, they’re not cyclical, and they have margin expansion,” Eisman told Bloomberg. “And now Zillow’s getting into a business that’s capital intensive, cyclical, low margin, and in a recession, they’ll get killed.”

The bull case for Zillow’s new business model is rooted in Silicon Valley optimism, and the general belief that big data and algorithms, combined with massive scale, can transform the inefficient U.S. housing market.

The bear case argues that algorithmic house-flipping at scale is a recipe for disaster in a recession, or possibly even just a modest downturn, and worse yet, that Silicon Valley’s attempt to digitize real estate could wind up “flash crashing” the whole housing market. (More on that shortly.)

Zillow announced its home-flipping plans in 2018, and they were actually years late to the party. A new trend called i-buying — which stands for “instant buying” — was kicked off by a Silicon Valley startup called Opendoor back in 2014.

The i-buyer concept is using big data and algorithms to make instant robo-bids on homes that come up for sale. The algorithm determines the worth of the property based on factors like neighborhood, resale values, crime rates, square footage, demographic trends, and a number of other inputs. Then it offers the seller an instant deal. If the seller accepts, the i-buyer pays cash.

The margins for i-buyer transactions are razor thin. For example, in a Wall Street Journal article explaining the i-buyer phenomenon, a transaction is described where Zillow bought a house for $605K and sold it for $610K — less than a 1% markup.

Zillow and other i-buyers plan to augment these razor-thin margins by charging the seller a commission between 6% and 9% — essentially replacing the traditional real estate agent with an automated online transaction. The seller gets the benefit of a lightning fast sale without having to worry about walkthroughs or home repairs. The commission helps cushion the razor-thin margins.

Eisman sees big danger in the asymmetric nature of the transaction. He points out that if i-buyers are buying thousands of houses at a clip, motivated sellers will know when the algorithm is pricing a market incorrectly, or when an individual property is distressed or damaged in some way. This information asymmetry always favors the seller, who can choose whether or not to transact with the algorithm — which means i-buyers will constantly be left holding the bag.

Zillow and other Silicon Valley-backed players are frantically stepping up their i-buying pace. Zillow anticipates buying 5,000 homes per month in the next few years. Opendoor purchased 11,000 homes in 2018 and has raised an additional $1 billion to start buying even faster.

This fuels another risk: The possibility that i-buyers could “flash crash” the U.S. housing market.

The U.S. housing market is traditionally stable because transactions move slowly, because local real estate agents guide the process, and because home sales are dominated by families making long-term investment decisions.

If i-buyers ramp up to tens of thousands of home purchases per month, traditional real estate agents could be driven to the brink of extinction. And then, having taken over the market, if housing values drop modestly or mortgage rates spike, i-buyers could use warning signals from their big data analytics dashboards to pull back from the market en masse, creating a Wile E. Coyote moment where home prices go into freefall.

“You should be able to sell a home within a handful of clicks,” says Eric Wu, the CEO of Opendoor. For some, that sounds like a dream. Under the wrong circumstances, it could turn into a national nightmare.

Zillow has admitted it didn’t want to get into i-buying in the first place. Zillow’s executives were very aware of the conflict of interest with real estate agents, who are still their prime advertising base.

But Zillow felt compelled to enter the business as a result of industry peer pressure. Along with multibillion-dollar-backed Silicon Valley startups like Opendoor and Offerpad, even old school traditional retail brokerages like Keller Williams and Coldwell Banker are now ramping up i-buyer programs. Zillow felt it couldn’t afford to be left behind.

Zillow has also admitted it doesn’t see real profits in the i-buying model. The hope is basically to run the home-flipping business at a little bit better than breakeven, and then earn a profit from mortgage lending and other services layered on top, which is why Zillow acquired Mortgage Lenders of America last year.

So, the bull case for Zillow, and the bull case for the i-buying model in general, is that Silicon Valley can throw billions of dollars plus big data and algorithms at the old school U.S. housing market. This means taking on huge levels of inventory risk, financial leverage risk, and asymmetric transaction risk without messing things up.

The bear case, as Steve Eisman points out, is that home-flipping is a low-margin, capital-intensive, high-risk business that tends to get killed in recessions, and furthermore that the whole i-buying concept was only made possible by a flood of cheap capital giving Silicon Valley the ability to recklessly fund whatever it wants. In a downturn, that flood of capital becomes a dry riverbed.

As to how i-buying will fare in a real downturn or recession, nobody knows. But it’s possible we could find out soon, because hot home-flipping markets are cooling down fast.

In the fourth quarter of 2018, home-flipper losses — transactions where the flipper was forced to bail at a loss due to carrying costs — were at their highest level since 2009, according to analysis from real estate firm CoreLogic. In the hot San Jose area, as an example, 45 percent of flips lost money.

|

If you’re deeply skeptical Zillow can make the i-buyer business work, long-dated puts could be a worthwhile investment. And even if you’re neutral, a bearish position on Zillow could serve as a hedge against the possibility of a sharp economic downturn.

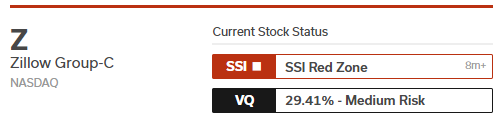

If Eisman is right, a recession would crush the i-buying model, and Zillow’s capital-intensive financial exposure to housing inventory could crush the stock as a result. Zillow (Z) is currently in the red zone with a medium-risk VQ.

As always, we’ll continue to watch the markets for potential opportunities like this and let you know what we find. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy the long Memorial Day weekend and take a few moments to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom.