There are few things more obnoxious than dieting and nutrition advice. The more you dig for answers, the more confusing things get. The findings conflict with each other. The recommendations are all over the map.

For example, one guy, a doctor or a Ph.D., tells you whole wheat grains are a bedrock staple. Another Ph.D. says grains are toxic for some impressive-sounding reason — because the casing of the wheat kernel was designed to be hard to digest and pass through the system, for example — and so you should never eat grains at all.

These conflicts go on and on. One study says load up on protein, another says too much protein is toxic. One diet says fruit is great, so eat huge amounts of fruit. Another one says fruit is just concentrated sugar in another form due to over-engineering. (Your great-great-grandfather’s apples weren’t nearly as sweet.)

It’s exhausting because the advice all conflicts — there are countless “scientific studies” that directly contradict each other — and yet everyone is pounding the table. At least half of it is nonsense, but you can’t tell which half.

Unfortunately, conventional investment advice has a similar profile. If you try to gather up sound investing wisdom from multiple sources, you will run smack into this problem.

A new academic study provides a hilarious example.

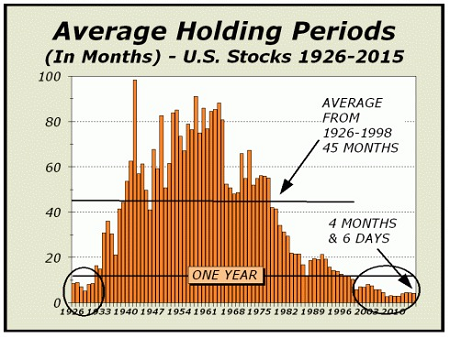

To set the stage, take a look at the below chart via the Alan Newman “Crosscurrents” newsletter that was published in 2015.

|

The chart shows, in a dramatic way, how the “average holding period” for a stock has fallen, from a peak baseline of 80 to 90 months (around seven years) in the 1950s to just four months in 2015.

The received conventional wisdom is that we — meaning the collective investing “we” — have all become a bunch of trigger-happy short-term gamblers.

You can practically hear a cranky old-timer yelling about how messed up things have gotten. “Nobody holds a stock anymore! Nobody appreciates the patience of a sound investment process! Get off my lawn!”

Ok, here is the hilarious part. As reported by Institutional Investor, a new study of fund managers says that returns are being hurt by the exact opposite problem. The managers are holding onto their positions too long. Via Institutional Investor, emphasis ours:

…[The finding is based on] new research from Essentia Analytics, which analyzes the decisions of fund managers based on behavioral science. The firm found that for all the hype about active manager underperformance, these managers actually do generate alpha, “well in excess of the fees they charge.” The problem: They tend to give all of it back, and then some, by holding on to their positions too long.

Just sit back for a moment and relish how hilariously goofy this is.

On the topic of investors and fund managers being too short-term and not holding their investment positions long enough, there have been enough preachy, finger-wagging articles printed in the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Smart Money, and other similar outlets to kill a million trees.

And yet here is a reputable study, cited by Institutional Investor, essentially saying, “Yeah no, they are holding on too long.” More specifically the report language reads:

“Investors often hold on to positions too long (a consequence, we believe, of the endowment effect), diminishing or eliminating whatever excess returns they were able to generate early on.”

“Don’t give back your gains” seems like common sense.

The fact that today’s fund managers have tried so hard to avoid the sin of short-termism that they actually went the other way — sitting around hurting their portfolios by hanging onto duds — is so absurd it is almost laugh-out-loud funny.

So what is the lesson? Don’t hang onto a stock too long if performance goes down the drain? That’s a good idea, but it isn’t the lesson.

The lesson is to ignore conventional investment advice, including the preachy stuff you find in the pages of “respectable” newspapers and financial magazines.

As with nutrition science and dieting advice, a lot of it conflicts and half of it — at least — is nonsense.

The way around this is to do your own homework, or otherwise find a consistent source that you trust to be logical and credible (and ideally both). With nutrition and dieting, if you work at it, you can find principles that are sound and seem to work for you. With investing, it’s the same.

In terms of when to sell a stock, by the way, the whole short-term versus long-term debate is a red herring. The thing to do is to have a logical system — a means to keep yourself involved in a winning trend, and a rational set of rules for getting out if the position goes bad. Then the time frame — be it three months, three years, or three decades — winds up taking care of itself.

TradeSmith Research Team