Global financial markets are facing a stark reality this week.

- To save lives during an outbreak, the health care system has to function.

- To keep the system functional, the caseload has to spread out over time.

- To spread the caseload over time, the rate of early cases must be slowed.

- To slow the rate of early cases, the economy must be sacrificed.

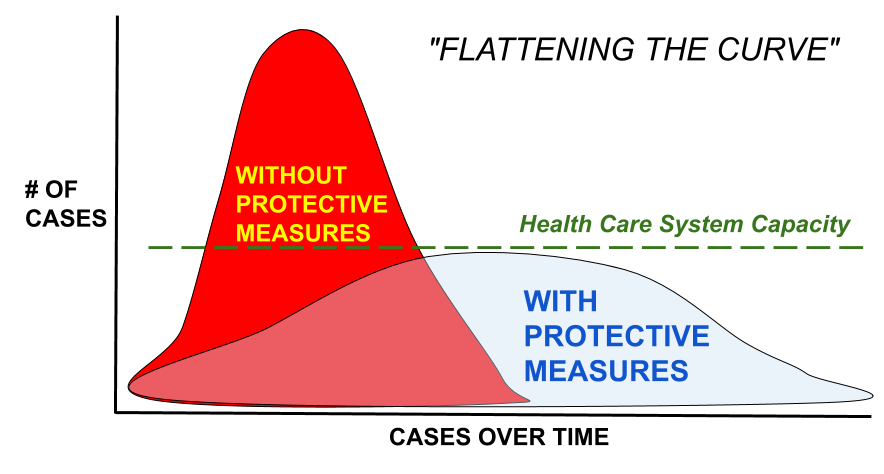

The term to describe this process, now trending globally, is “flattening the curve.”

It comes from a visual graphic conceived by The Economist. Our version is below.

Every country’s health care system has a maximum capacity. By “flattening the curve” of cases over time, the functionality of the system is maintained. Without doing this, the caseload spikes and the system breaks.

The United States, for example, has roughly 1 million hospital beds. Out of those 1 million beds, around 70% are filled at any given time.

This means that, in theory, the U.S. has 300,000 open hospital beds, give or take.

With a big-enough surge of coronavirus cases — 15-20% of which require hospitalization — all of those beds could be filled. If a severe shortage then develops, disaster follows.

The graph captures the idea of what happens with an early surge. If there are too many cases all at once, the health care system is overwhelmed. In contrast, if the cases are spread out — if the curve is flattened — the system can handle them.

In addition to hospital beds, the U.S. is facing a shortage of masks, ventilators, and staff.

All of these shortages will be easier to handle if the U.S. can flatten the curve, which buys the system more time. In a crisis, buying time is everything: time to ramp up mask production; time for equipment and beds to become available; time for staffers to recover; time to develop a vaccine, and so on.

The way you buy time is by flattening the curve.

It’s not just a matter of how many Americans get sick. It’s how soon they get sick. If an overwhelming number get sick all at once, the system fails. If the distribution is spread out, the system can still function.

If the curve is not flattened, the result is a nightmare. On the graph, the tall red spike represents an overwhelming flood of early cases.

When the spike happens, patients wind up dying for unacceptable reasons. Standards of treatment go out the window. Ambulance arrivals take 80 minutes rather than eight minutes. Non-terminal patients can’t even get diagnosed, let alone treated. Doctors and nurses wind up collapsing on their feet from exhaustion.

None of this is theoretical. Horror stories of a broken health care system are pouring out of Italy now. And in terms of coronavirus case patterns, Italy is only a week or two ahead of the United States.

This is where sacrificing the economy comes in.

To flatten the curve — to keep the health care system functional by spreading out the caseload — the economy has to be flattened, too. A huge portion of economic activity has to be sacrificed.

That sacrifice is the unavoidable result of “social distancing,” a phenomenon where citizens avoid each other like the plague (no pun intended).

For example, consider some recent cancellations:

- The SXSW “South by Southwest” conference, normally held in Austin, Texas, was cancelled for the first time in 34 years.

- The entire NBA season has been postponed (cancelled) until further notice.

- Multiple other large-scale conferences, concert festivals, and industry gatherings were cancelled.

That short list alone represents billions of dollars in lost revenue and commerce. And that is just the tip of the iceberg.

When you look across sectors and industries, and think about the countless ways “social distancing” taken to extremes can halt the flow of a service-based economy, the lost revenue numbers pile up fast.

And in order to save the health care system — to flatten the curve in a truly meaningful way — the sacrifices have to go much further than the mere cancellation of festivals and sporting events. All activities that enable the spread of infectious disease have to be curtailed as much as possible.

This winds up jeopardizing every source of commerce that involves social gatherings. Bars. Restaurants. Shopping malls. Family outings. Employee gatherings. All of it.

If it involves dense crowds of human beings in any way, close-quarter activity becomes a risk in a time of pandemic crisis. When a health care system breaks down, society breaks down. That makes every effort worth it to keep the breakdown from happening.

The hard part is that curve-flattening is economically brutal when done to full extent. Trillions of dollars in commerce can be lost. Hundreds of thousands of businesses, small, medium or even large-sized, can go bankrupt from lost income and missed debt service payments. Layoffs can run into the millions, or even the tens of millions.

But if the disease is infectious enough, and deadly enough, taking no action can be worse.

Italy serves as a warning on this front, and a foreshadow in respect to what can happen. Just look at the progression of steps the Italian government went through, each one more desperate than the last:

- At first, the Italian government tried to get by with conventional measures and stern warnings.

- As the health care system started to buckle, 17 million citizens were put on lockdown.

- When partial lockdown was not enough, the entire country of 60 million was put on lockdown.

- When full-country lockdown fell short, the government ordered the closing of all shops other than pharmacies and food outlets, along with fines and jail time for quarantine violators.

“We have run out of time,” said Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte on March 10. What he really meant was that Italy’s health care system was collapsing. When people are dying in droves, extreme measures must be taken, period.

Outside of Italy, Western leaders still aren’t processing the danger.

In Manhattan, for example, New Yorkers are still allowed to attend Broadway shows and cram into jam-packed subway cars. (The advice given is to seek out a less-crowded car if possible. Really?)

If New York was serious about flattening the curve, all forms of crowd-inducing activity would be halted — not with suggestions or even pleas, but rules and harsh fines — even though the economic cost would be devastating.

And this isn’t to pick on New York in any way. It’s just one example. That same kind of trade-off applies to the entire U.S. economy.

Doing all we can to slow the proliferation of early coronavirus cases, with social distancing measures taken to extremes, could cost the economy trillions.

And a big chunk of that cost would likely need to come as a form of economic relief, to help out all the service workers who lose their jobs (and business owners who lose their businesses).

We know what seems to be working in places like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, where curve-flattening measures were embraced early and aggressively. We also see what Italy has been forced to do in a series of last-ditch desperation measures, where curve-flattening was neglected to the point of being too late.

Within the United States, we haven’t acted decisively yet because nothing has forced our hand.

And yet, a forced decision is coming.

The U.S. can choose to endure significant economic pain here and now — in the name of flattening the curve to safeguard the health care system — or it can risk far worse pain as the health care system breaks.

The markets are processing the reality of this hard choice. It holds not just for the U.S., but also the U.K. and other countries in Europe, which is partly why stock markets are registering historic levels of decline on multiple continents.

A democracy cannot stomach an imploding health care system, as Italy found out the worst possible way.

And so, in the end, the U.S. is likely to take draconian curve-flattening measures no matter what, going far beyond the cancelling of concerts and NBA games.

The question is whether that’s done earlier, with a firmness of resolve from the top down, or later down the road, as a last-ditch Hail Mary in the midst of systemic catastrophe.