The Special Purpose Acquisition Company, or SPAC for short, had a supernova kind of year in 2020.

The after-effects could be felt, in a bullish way, well into 2021, as hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of SPAC-driven merger and acquisition (M&A) activity waits to be unleashed.

In 2020, the total amount of capital flowing into SPAC deals smashed all previous records, besting the prior record year (which was 2019) by nearly 10-to-1.

Alternately known as “Blank-Check Deals” or “Backwards IPOs,” the SPAC, as an investment vehicle, has a comparable feel to the joint-stock offerings of the 1720 South Seas bubble.

In 1720, the year that a speculative frenzy surrounded the South Sea Company, there was so much investor froth and fervor afoot that fly-by-night operations sprang up left and right to take advantage, offering a wide array of exotic and bizarre schemes.

The SPAC has two basic forms, with a different nickname for each.

As a “Blank-Check Deal,” the SPAC is a way to raise money for an unknown acquisition target.

In this manner, investors give the SPAC manager carte blanche to buy something, typically within the next two years, and fund the SPAC with hundreds of millions of dollars (or billions of dollars) to do so.

One could call it pig-in-a-poke investing, except the poke has no pig in it. There is nothing there until an acquisition is made. The idea is that the SPAC manager is wise enough, or experienced or connected enough, to make a deal that investors will make money on.

The second form of SPAC, “the backwards IPO,” is a means of going public without really going public.

When a young company (or even a brand new company) comes to the market via SPAC, they skip the normal initial public offering (IPO) process.

Instead of going public the hard way (with an IPO), to do a SPAC, the hot new company does a reverse merger with a sleepy public company that is already exchange-listed, and takes over the existing listing before changing the symbol and the name.

Going public through the SPAC route has multiple advantages:

- It is often faster than a typical IPO process.

- It can generate huge (yet opaque) profits for the SPAC manager.

- It lets the company sidestep rigorous IPO disclosures.

But there is another loophole advantage for SPACs that is larger than all other advantages combined.

It is such a jaw-dropping loophole, in fact, one wonders why the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has allowed it to exist.

With an IPO, there is a strict “quiet period” prior to the official launch. Also with an IPO, corporate executives are not allowed to talk up future prospects of the company in an unproven way.

You aren’t allowed to aggressively “hype” an IPO, in other words. There are limits on what company executives can say and do. For the most part, respectable Wall Street analysts are supposed to make the sales pitch for them, with a rigorous prospectus outlining the risks.

With the SPAC, there is none of that. If you are doing a SPAC, you can say whatever you want.

You can make wild future projections about revenue years into the future, go on hundreds of YouTube channels, podcasts, and investor message boards, and hype to your heart’s content.

The “hype free-for-all” angle, in our view — meaning the ability to promote with abandon, and no holds barred — is probably the biggest reason that SPACs exploded in popularity in 2020. Here are a few examples of what we mean:

- Fisker, an electric vehicle (EV) company in the mold of Tesla, did a SPAC worth $3 billion. In raising the funds, the founder projected $13 billion revenue by 2025 (up from zero in 2020), as based on reservations for a vehicle it plans to sell in 2022 (which doesn’t exist yet).

- Chamath Palihapitiya, a noted and outspoken venture capitalist, aggressively pitched a SPAC acquisition of Opendoor, a robo-buyer of homes sight unseen. In a CNBC appearance, Palihapitiya confidently predicted Opendoor’s revenue would more than double by 2023. The shares of the SPAC rose 35% in a day.

- After Nikola, another EV company in the mold of Tesla, said it was going public via SPAC in March 2020, the company’s founder did interviews with countless podcasters and YouTubers, boldly predicting the company would soon be making billions in revenue. Nikola’s shares peaked at $80 and finished the year at $15.26, a more than 80% decline.

According to Bloomberg, the first-ever SPAC deal goes back to 1993.

But the SPAC concept never took off in the 1990s, perhaps because investors were too skeptical, or asset managers were gun-shy of trying something so brazen, or both.

In the first decade of the 2000s, the peak SPAC year was 2007 — also the height of a private equity bubble and housing bubble — where SPACs saw $7 billion worth of deals.

That sounds like a rounding error now, but it was eye-brow raising at the time. Then the global financial crisis killed off speculative activity for a while, and SPAC deals went dormant until 2019 — at which point they exploded, and then in 2020 went supernova.

In 2019, according to research firm Dealogic, there were $13.5 billion worth of SPAC deals. In 2020, there were at least $131 billion worth of such transactions, nearly 10 times the 2019 amount.

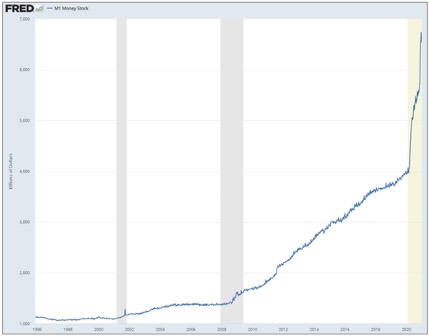

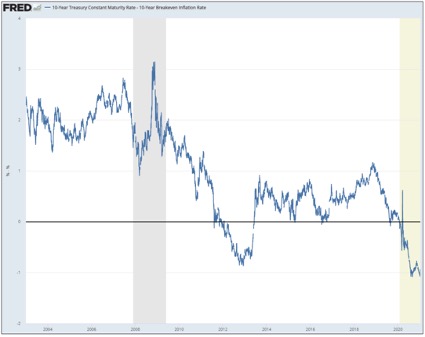

Why the SPAC supernova? Because the SPAC is the perfect vehicle for a hyper-speculative environment.

When investors are willing to throw money at anything, almost anyone with a strong enough pedigree, or plain old celebrity name recognition, can cash in with a SPAC offering.

And boy, is everyone trying. Some notable SPAC deals include a famous Major League Baseball manager (Billy Beane, the subject of the book-turned-movie Moneyball); a former astronaut (Scott Kelly); a former NBA all-star (Shaquille O’Neal); and a former Republican Speaker of the House (Paul Ryan).

So on the one hand you have celebrities and hedge fund managers turning fame or reputation (or both) into a chance to print money — by way of being handed other people’s money in a SPAC wrapper — with a promise to make some acquisition that will be truly great (again, with nobody knowing what it is).

And on the other hand, you have high-flying companies of the sexy technology variety — electric vehicles, self-driving, and forms of futuristic tech — with founders and hype-men able to paint visions of billions flying in through the window, taking their message directly to small investors via YouTube channels and podcasts and message boards. (Boy oh boy, are there message boards.)

It is not hard to see how all of this ends. The technology changes but people stay the same.

We are now witnessing one of the most brazen mania-driven money grabs in all of history, right up there with the South Seas bubble, Holland’s Tulip Mania, the 1929 boom, and any other mania one would care to name.

The one possible exception would be Japan’s late-1980s boom — but if real estate sees enough of a frenzy, maybe we’ll eclipse that one, too.

All of this sounds like a warning that “the end is coming.” And it may well be. But we can’t say when with any kind of confidence, because there is plenty of liquidity still available to keep the party going.

Because the typical SPAC has a time limit for making an acquisition with the cash it has raised, we can expect a flood of cash to power a new wave of M&A activity in 2021.

According to estimates from Goldman Sachs and Bank of America, the SPAC M&A wave could be $300 billion to $400 billion in the coming year. And then, too, behind that wave, you have private equity fund managers sitting on as much as $1.6 trillion worth of dry powder not yet deployed into deals.

That tells us the SPAC supernova — and the epic market mania we are now all living through, on par with the great all-time manias all through the ages — probably isn’t over yet.