The Berkshire Hathaway annual letter — penned, as always, by CEO Warren Buffett, now 90 years old — came out this past weekend. If you haven’t read it yet, you can do so here.

Reading the Berkshire letter, and hunting for easter eggs of Buffett bon mots and insights, has become a kind of annual tradition for much of the financial world. Analysts, money managers, journalists, and investors of all stripes tend to read it the weekend it comes out, even if they own no shares.

Your editor is one such reader: Though never a shareholder, we’ve been perusing the Buffett letters for nearly 20 years. We also have all of the old letters on file, dating back long before we were born. The best one of all, in our view, is the Buffett Partnership letter covering 1965, available here.

The 2021 letter felt somber and restrained compared to past years. This makes sense, given what America and the world had to go through in 2020.

Still, in terms of pessimism and dark warnings — far from the normal fare for Buffett — this passage on the “bleak future” for fixed-income investors stood out:

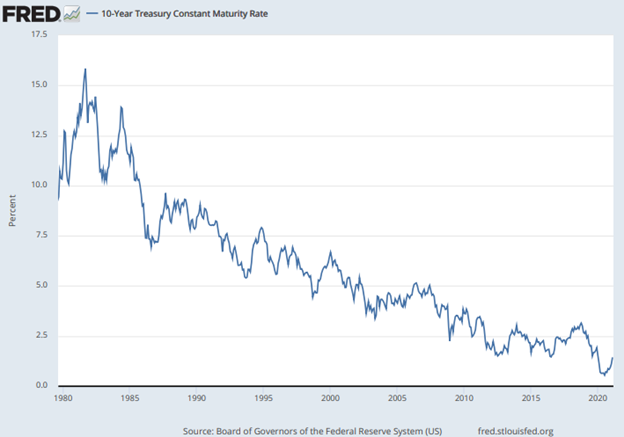

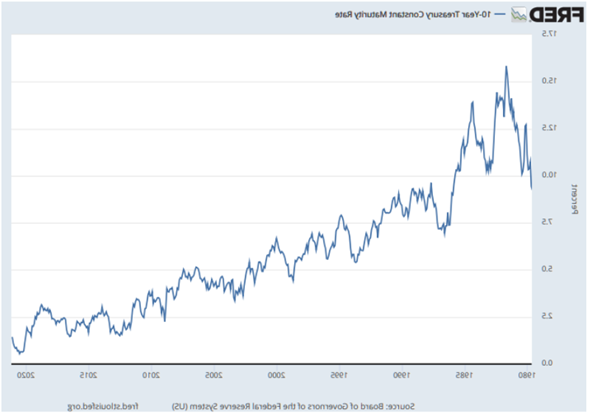

[B]onds are not the place to be these days. Can you believe that the income recently available from a 10-year U.S. Treasury bond – the yield was 0.93% at year end – had fallen 94% from the 15.8% yield available in September 1981? In certain large and important countries, such as Germany and Japan, investors earn a negative return on trillions of dollars of sovereign debt. Fixed-income investors worldwide – whether pension funds, insurance companies or retirees – face a bleak future.

Per Buffett’s calculation, over the course of almost four decades — from September 1981 to year-end 2020 — the yield on the 10-year note fell by 94%.

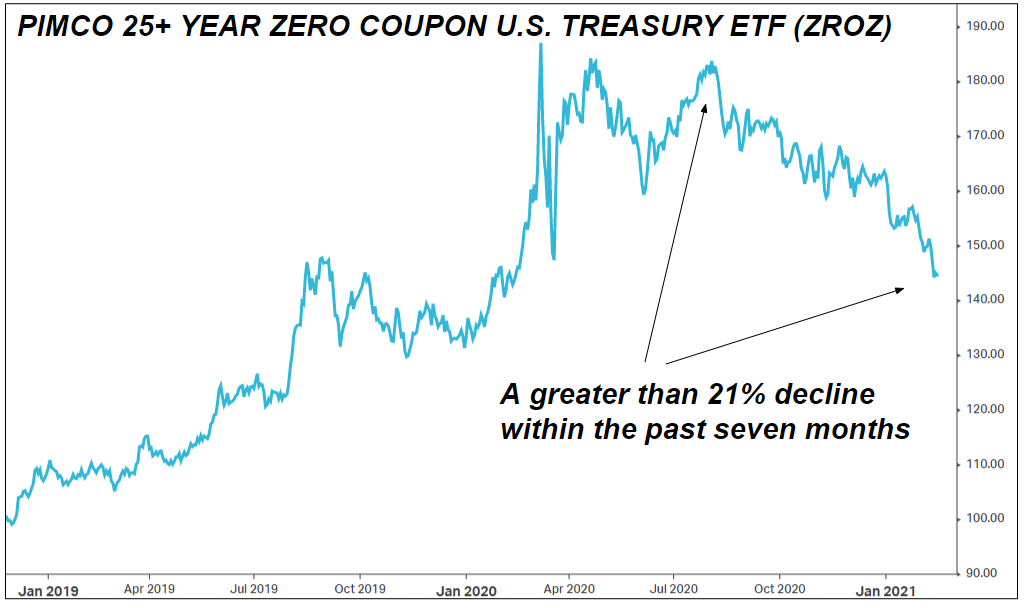

In regard to falling yields, here is another remarkable stat per Chris Bloomstran, the president and chief investment officer of Semper Augustus: As of Feb. 27, the price of the U.S. 30-year Treasury bond had fallen by more than 16% in three months — a drop that erased 10 full years’ worth of coupon payments. Also per Bloomstran, the 10-year gave up 7 years’ worth of coupons in that time.

Imagine clipping coupons on your government bonds for a full decade — then taking a hit on the principal worth all of the payments and then some, over the course of just 12 weeks. Now imagine trying to be a government bond investor moving forward.

For holders of long-dated U.S. Treasuries, the pain is increasing because the U.S. economy is reflating, powered by vaccine optimism, pent-up demand, and a tsunami of fiscal stimulus. Economic growth of the rip-roaring variety is coming, with inflation to follow on the heels of that.

If you’ll pardon the cheap rhyme, the interest-rate mantra “lower for longer” now looks “wrong and wronger.” Per data from Bespoke Investment Group, the 2021 sell-off in the Merrill Lynch 10+ Year Treasury Index has already produced the third-worst percentage since records began in 1988 — and the year is still young.

Then, too, Buffett’s harkening back to 1981, and a 94% decline in yields over nearly 40 years, is a sobering reminder of how far the pendulum has swung. The chart below, via FRED, shows the four-decade journey of the 10-year yield from 1980 to today.

It is hard to beat the 10-year yield for a vivid illustration of what Ray Dalio calls “the long-term debt cycle.”

The Long-Term Debt Cycle is the cyclical pattern by which interest rates and inflation pressures tend to fall, even as debt and leverage levels rise, for decades at a time.

At the beginning of the long-term debt cycle — which had its genesis in 1981 — inflation was sky-high, while debt and leverage levels were low.

Interest rates peaked in 1981 because that was the year Paul Volcker, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, finally “broke the back of inflation” in a way investors could acknowledge.

Volcker’s efforts to kill off inflation, through a multi-year period of painfully high interest rates, were part of what cleaned out the debt and the leverage. The United States went through not one, but two recessions in the early 1980s, spaced about 14 months apart, as the price of borrowing went through the roof.

But Volker’s successful anti-inflation campaign, coupled with low debt-and-leverage levels, was the very thing that allowed a new long-term debt cycle to kick off.

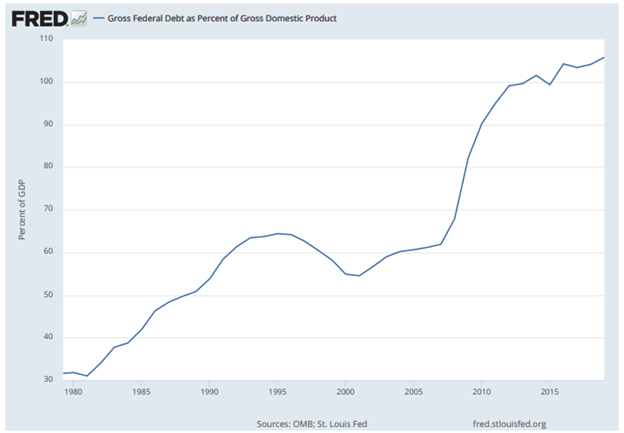

The build-up of debt to GDP from 1980 onward, as shown in the FRED chart below, is a sort of inverted image of the falling 10-year yield. That is because, in a standard long-term debt cycle, debt levels go up as inflation and borrowing costs go down.

The “bleak future” that Buffett warned of for fixed income investors relates to what happens when the long-term debt cycle reaches its farthest point.

Think of a giant, slow-moving pendulum that swings in the same direction over a 40-plus-year period. Over that entire window of time, bond yields and inflation pressures are falling, even as debt and leverage levels rise.

Once the pendulum starts to swing the other way, a multi-decade trend in the opposite direction occurs. Instead of falling for decades on end, yields go into a pattern of rising for decades on end (which means bond prices fall); and instead of debt and leverage building up to ever-higher levels as a percentage of output over time, there is a far less pleasant multi-decade period where debt and leverage levels are cut back (or inflated away) to a lesser percentage of output over time, rolling back the previous extreme.

Then, once the pendulum has swung all the way back, it swings forward yet again, a kind of permanent oscillation between high interest rates versus low, coupled with low debt levels versus high. And because a nation’s economy is immortal — assuming the nation continues to exist — these generational patterns of build-up and roll-back can repeat ad infinitum.

What a majority of investors haven’t yet realized is that their entire personal experience in markets — going all the way back to 1981 — is geared toward the pleasant half of the long-term debt cycle.

All that they know on a gut-feel basis — unless they were active market participants in the 1970s — is that left-to-right pendulum swing where interest rates fall, as debt and leverage rise and rise.

Buffett’s warning to fixed-income investors is a reminder we are headed for the less-pleasant half of the long-term debt cycle — the multi-decade period where interest rates rise and rise, and then rise some more, as governments, corporations, and consumers either actively reduce their debt loads or see the value of those debts inflated away.

Then, too, inflation is a part of the process because the debt adjustment almost always happens more via inflation than hardcore belt-tightening: It is just easier to reduce the debt load via printing press, which reduces the percentage ratio of debt-to-output over time. That tendency also explains why inflation will likely roar higher again — with interest rates rising up with it — over the next decade or two (or three, or four).

Just for fun, we took the 10-year yield chart and flipped the image horizontally (below), to create a visual picture of how the next 40 years might look if the long-term debt cycle retraced its steps perfectly. It’s never that simple, of course, but as a mental exercise, it’s worthwhile trying to imagine interest rates following a path like the one below.

The bottom line is that very few investors are ready for the world that is coming.

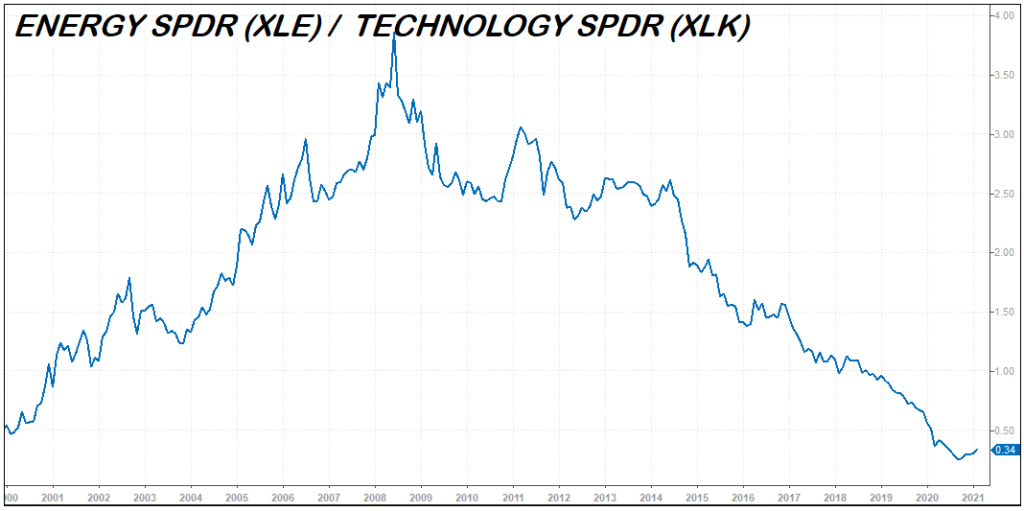

With “lower for longer” becoming “wrong and wronger” as the U.S. prepares for emerging-market-like levels of growth in the year ahead — and the Federal Reserve signaling it is fine with a jump in long-term yields, at least for now — dislocations in vulnerable areas of the stock market are likely just beginning.