Believe it or not, there is a plausible scenario where the stock market sees a retest of the March lows before 2020 ends. It isn’t a far-fetched scenario, either. Though not the base case, another 30% or greater drop in the S&P 500 — and the Nasdaq — could happen before the year is out.

If that sounds bizarre, well, that’s because it is. Remember, though, that all of 2020 has been bizarre, and the year isn’t over yet.

We are living through one of the strangest years in financial history — and arguably one of the strangest years in history, period, for that matter — with more yet to come.

In terms of factors putting the market at risk, so much so that they could fuel another massive drop, there are at least three big ones.

- The first major risk factor is the 2020 election. This election carries an extraordinary amount of uncertainty, due to the expected closeness of the outcome and a question mark as to whether the opposing party will accept the results. You will hear more about this, including details of a free webinar and a special report covering post-election market scenarios, in the coming days.

- The second risk factor is a lack of follow-through from Washington on additional stimulus and COVID-related unemployment relief. Due to a lack of agreement in the halls of Congress, the real economy (Main Street) is getting the rug pulled out from under it as conditions get truly tough.

- The third risk factor relates to online trading platforms (OTPs), the Robinhood-enabled bull market powered by an army of new day traders, and the staggering amount of money that has poured into call options. The funds that drove this phenomenon were powered by Uncle Sam, leaving the question, “What happens when the call-option money runs out?”

Let’s talk some more about call options first. We wrote a while ago about the “bored in lockdown” theory, and the manner in which Silicon Valley engineered a retail investment boom.

We also explained how a retail investor strategy of aggressive call-option buying has added extra rocket fuel to the market, because near-dated call options magnify the leverage of any purchase.

Imagine taking a full tank of gas and, instead of driving 500 miles with it, running it through a kind of nitro-burner that lets your car go 200 miles an hour for a distance of about 10 miles, and then all the gas is gone. That is what near-dated call options can do.

Buying such options en masse, with the goal of “profits or bust” in a literal sense — you either make a huge score quickly or your money is gone — has become the hot new thing for Robinhood retail traders, along with users of other zero-commission OTPs.

This is why we have seen jaw-dropping moves in retail-favored names like Salesforce (CRM), up more than 28% in a single day post-earnings, and Zoom Video Communications (ZM), up 40% in a single day post-earnings, along with gut-wrenching, double-digit declines in the days that immediately followed.

This insanity has been largely fueled by a frenzy of odd-lot call-option buying, meaning, retail trader options purchases of 10 contracts at a time or fewer. And the data bears this out.

“The volume of trading in single stock options recently topped the volume of regular shares for the first time,” The Wall Street Journal reports. “As of the end of August, single stock options volume made up more than 120% of the volume of the shares, up from around 40% three years ago.”

The call options are seeing more volume than the shares. That has never happened before. Not in 1999, not in 1987, not in 1929, not ever.

“It has been a record year for options volumes,” the WSJ continues. “So far in September, about 35 million single-stock and ETF options contracts have changed hands on an average day, up about 92% from the same month last year.”

The problem with bull markets powered by a kind of maniacal frenzy is that a shift in sentiment — or a lack of funds — can make the frenzy suddenly disappear. When this happens, look out below.

Stocks with nosebleed valuations that aren’t supported by real fundamentals or real conviction — only traders playing a game of hot potato in terms of who buys last — can suddenly be left high and dry by a crowd that leaves the scene, either because the crowd ran out of money or just shifted their interest elsewhere.

We have actually seen this phenomenon over and over again in emerging markets. It is so common that the term “hot money” was invented to describe it. A country will become a hot destination in the eyes of overseas investors, large volumes of capital will rush in, and the investable assets of the country will see big run-ups in price.

But then something will happen, maybe a mini-crisis or a change in monetary policy back home, and the hot money will withdraw, causing asset values to suddenly implode. This has happened so many times that the financial authorities in most small countries have developed a love-hate relationship with foreign investor flows, due to their inherent lack of stability.

In terms of current market valuations, we would argue that the “hot money” supporting retail call-option buying and pushing up tech stock valuations is potentially a lot like that, only far, far worse.

The level of frenzy as evidenced by call-option buying reaching never-before-seen levels, smashing all prior records to bits, would be notably worrisome on its own. But the picture gets worse when we remember where the play money came from.

The “bored in lockdown” stampede into stocks was fueled by stimulus checks and unemployment benefits, a kind of fiscal helicopter drop that went directly into the stock market.

We know this because Envestnet Yodlee, a large-scale aggregator of U.S. consumer financial data, had survey results showing that stock market purchases were one of the top uses of the $1,200 stimulus checks.

The unemployment top-up, providing unemployed Americans with an extra $600 per week, was also a very big deal in terms of consumer financial impact. In fact, between the stimulus checks and the unemployment top-up, some households actually earned more in the lockdown months than they ever had before.

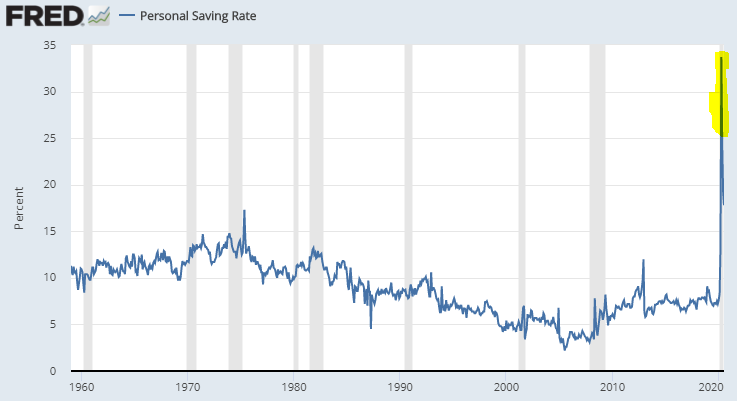

We can see the extraordinary impact of stimulus checks and topped-up unemployment benefits by looking at the personal saving rate.

The personal saving rate (PSR) tracks the percentage of income that Americans save after taxes and discretionary purchases. To put it another way, the PSR is the percentage of every dollar that goes into the piggy bank. The FRED chart below shows the PSR dating all the way back to 1959. The yellow highlighted area shows the extreme spike in the PSR created by the fiscal helicopter drop of stimulus and unemployment top-ups.

Prior to 2020, the highest the PSR had ever climbed in a single month was 17.3% in May 1975, meaning that Americans saved roughly 17 cents out of every dollar.

In April 2020, meanwhile, the PSR rocketed to 33.7%, nearly double the prior record. How did this happen? Because Uncle Sam dumped trillions directly into the U.S. economy, that’s how. The stimulus checks and the topped-up unemployment benefits, delivered at the same time, were a never-before-seen cash infusion.

That cash from Uncle Sam provided rocket fuel for the stock market. Lower-income households used the government funds received to do things like buy food and pay rent.

But millions of middle-income households, including plenty of millennials, didn’t really have any short-term need for the funds they had qualified for. So they jumped into the stock market.

By July, the PSR had fallen to 17.8%, a decline of close to half. That is because the stimulus checks were a one-time thing, the unemployment top-ups were drawing to a close, and the pain of layoffs and permanent furloughs was increasing.

Now, in September, we are on the other side of a “fiscal cliff” for tens of millions of Americans, who saw their unemployment top-ups run out weeks ago, even as wave after wave of job losses in the service sector are becoming permanent and eviction moratoriums are being lifted.

Do you see the problem here? The U.S. government provided a stunning amount of fiscal support, at a scale never before seen, and then essentially shut off the taps.

Nor is this a problem for the stock market alone. It is a much bigger problem for the real economy, meaning Main Street rather than Wall Street.

Congressional negotiations for new rescue funds have ground to a halt. As of this writing, it looks like nothing will be coming in the month of September — even with 30 million Americans on some kind of unemployment aid, and tens of millions facing the prospect of eviction or bankruptcy.

And so, heading into the 2020 election, Washington and Wall Street are setting up a gruesome joint experiment that asks a question:

“What happens if you pull all the funding that helped the real economy stay afloat in the first place, even as COVID-19 cases gear up for a fall-winter resurgence in conjunction with flu season, ahead of a crisis-prone election where investors are deeply nervous, at a time when stock valuations are about as extreme as at any point in the past 100 years, with the whole thing powered by a frenzy of call-option buying that could evaporate or reverse at any time?”

Unfortunately, a plausible answer to that question is:

“You get a sudden collapse of bullish sentiment, combined with a cascade of sell orders that feeds on itself, with no buying orders to offset as the call-option money evaporates. This wipes out the Robinhood traders en masse, while causing other large investors to step completely to the sidelines as markets enter freefall — and a retest of the March lows is the result.”