John Maynard Keynes was not just a famous economist. He was also a world-class money manager and an inspiration to Warren Buffett.

In the 1930s, one of Keynes’ best-ever investments was a concentrated position in South African gold stocks. With the threat of fiat currencies weakening dramatically in the coming years, as central banks go back to emergency stimulus programs and cutting interest rates, we’ve got the opportunity to replicate Keynes’ greatest trade. Let’s take a closer look.

John Maynard Keynes is mostly known today for “Keynesian Economics,” the body of ideas and theory that came out of his 1936 magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest Rates and Money.

Keynes also wrote a book in 1919, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, that correctly predicted the onset of a second World War (because the victors’ terms after World War I were so harsh) and was instrumental in the Bretton Woods negotiations of the 1940s that set up an international currency system.

Keynes is far less known for being an excellent money manager, one of the best of his time. From the early 1930s onward, Keynes successfully managed portfolios for himself, several friends, two insurance companies, and the endowment of King’s College, his alma mater at Cambridge.

In his concentrated value-investing style, Keynes also had an influence on Warren Buffett, the greatest value investor of the 20th century. Buffett approvingly noted the following passage from a letter Keynes wrote in 1934:

“As time goes on, I get more and more convinced that the right method in investment is to put fairly large sums into enterprises which one thinks one knows something about and in the management of which one thoroughly believes.”

That is a good description of what the legendary investors in our Billionaire’s Club do today, allowing us to benefit from tracking and analyzing their positions with the help of software.

But before Keynes learned to become a value investor, he burned himself multiple times as a speculator.

In 1920, with the help of royalties from his first successful book, Keynes began trading currencies with 10X leverage and other people’s money. He was successful at first, but then got wiped out — at which point he raised more capital, went back into his positions, and made the modern day equivalent of millions.

Adjusted for inflation, Keynes himself had a net worth in the multimillions by the end of the 1920s, at which point he was speculating heavily in commodities like rubber, wheat, cotton, and tin. But once again, Keynes was way too leveraged, and he wound up losing 80 percent of his capital in the aftermath of the 1929 crash.

Having made and lost substantial fortunes multiple times, Keynes finally switched to the concentrated value investing style he would use for the rest of his life, and was overall successful from then onward.

At the time of Keynes’ premature death in the mid-1940s, his estate was estimated at 440,000 British pounds, the equivalent of more than $30 million in today’s money. He also had a fine art collection, appraised decades after his death, that was worth tens of millions. Last but not least, the endowment Keynes had managed for King’s College saw a 25-year compound annual return of 16 percent, crushing the UK market averages over that same time period.

Even as a value investor, Keynes was willing to make incredibly bold moves when he felt deep conviction. That is where his big trade of the 1930s comes in. In 1933, Keynes decided to plow two-thirds of his capital into South African gold stocks.

His analysis was both top down and bottom up. On the currency side, Keynes believed South Africa would be forced to depreciate its currency. A weaker currency meant that the profits of South African gold miners — earned by selling gold abroad — would rise sharply in currency-adjusted terms, leading to a dramatic increase in earnings per share. At the same time, from a bottom-up perspective, Keynes’ analysis showed the gold miners to be undervalued relative to their assets.

Gold stocks in general were an incredible investment in the 1930s. Keynes would have done even better, and had returns in the stratosphere, had he sold out his leveraged commodity plays and plowed into gold stocks years earlier.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average peaked in September 1929 and bottomed out in July 1932. From the peak to the trough, two years and 10 months in the making, the Dow saw a catastrophic decline of 89.2%.

In that same time frame, the share prices of Homestake Mining and Dome Mines — the most prominent U.S. and Canadian gold miners respectively — actually rose hundreds of percentage points, while increasing their dividend yields to boot.

Such performance would be stunning in a flat or modestly declining market. To see such performance over the 1929-1932 period, with the Dow in a catastrophic multi-year decline, is simply incredible.

Today, the conditions are replicated for Keynes’ big trade in South African gold stocks.

- The odds of substantial currency depreciation for multiple countries are high, as trade wars and heavy debt loads increase the odds of global economic downturn, or even a global recession.

- The currencies of emerging markets and commodity-producing countries, like South Africa and Australia respectively, are especially vulnerable to the prospect of a China slowdown.

- Central banks the world over, first and foremost the Federal Reserve, are moving toward a stance of cutting interest rates — and will resume currency-debasing stimulus programs if they truly get worried.

With regard to central bank actions, we have already seen a wild shift in sentiment.

Less than nine months ago, the Federal Reserve was expected to raise interest rates multiple times — the “normal” thing to do after 10 years of economic expansion with interest rates not far above zero and U.S. unemployment at the lowest levels in half a century.

But now, the overwhelming consensus is that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates — not raise them — and that multiple cuts could be happening soon. Most of the other central banks, large and small, are on a similar path.

This is bad news for fiat currencies, but good news for gold and gold stocks, as some of the nastier features of the 1930s (currency depreciation, trade wars, and a breakdown of international relations) are now being replicated.

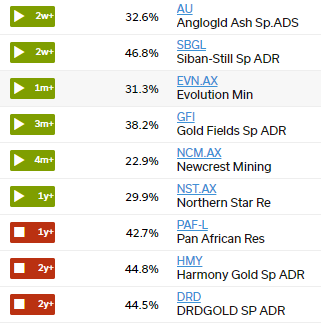

Below is a tracking list of South African and Australian gold stocks, all of which could rise substantially in the years ahead through a combination of currency depreciation, central bank stimulus, international turmoil, and a rising gold price.

|

You can monitor these stocks and set alerts with a Watch Portfolio in TradeStops.

You can also monitor the overall price trend of gold stocks — which have surged in recent weeks as the market anticipates interest rate cuts — via GDX, the Van Eck Gold Miners ETF, or GDXJ, the Van Eck Junior Gold Miners ETF.

If the upcoming decade of the 2020s bears any resemblance to the 1930s, it may not be a fun time — but we’ll have an opportunity to profit by replicating the 1930s’ greatest trade.