Eric Arthur Blair — better known by his pen name, George Orwell — is the British author who wrote the timeless classics Animal Farm and 1984. Phrases still in use today — like Orwellian, Big Brother, and Thought Police — are a result of those novels.

Orwell was also known for his essays. In 1946, the year after World War II ended, he wrote the following in a piece titled “In Front of Your Nose:”

“We are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on a battlefield.”

Orwell also has a famous quote: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

Long before the phrase “cognitive bias” gained attention in the 1970s, Orwell and many others (all the way back to the ancient Greeks) knew something basic about human nature.

It can be very hard to see what is “in front of your nose” — in other words, the glaring evidence right in front of you. There are countless ways to be distracted or misled … or focused on the wrong thing … or thrown off balance by emotion … or a dozen other things.

At the same time, every so often and seemingly like clockwork, there’s an example in the news where human judgment fails spectacularly.

Such-and-such person makes a decision (or a string of decisions) so terrible that the age-old question arises: “How could anyone make such an obvious mistake? How in the world did that happen?”

They probably failed to see “in front of their nose.” And it was probably due to cognitive bias.

Cognitive biases help explain the “why” behind certain bizarre quirks of human nature.

They can be described as “systemic patterns of deviation” from rational thought.

These biases are “systemic” in the sense they are built into the brain, which means everyone has them as part of the brain’s default setting. They are not glitches or flaws in day-to-day functioning, but a result of the brain’s architecture.

Cognitive biases are literally everywhere. Anyone with a brain is susceptible to them.

But how do cognitive biases make it hard to see something obvious?

Take confirmation bias — one of the better-known biases (there are hundreds of them) — as an example. Confirmation bias is the tendency to filter information in a way that supports a desired belief.

If you deeply want to believe “X,” for example, your brain will seek out and register information that confirms the validity of X. At the same time, your brain downplays or ignores inputs that go against X.

The stronger your desire to believe something, the more powerful this effect becomes.

Confirmation bias can sometimes be so strong that it creates a reality distortion field — where the person in the grip of the bias is no longer able to process reality accurately.

In markets, this can get expensive. The problem is that different cognitive biases can combine and reinforce each other, leading to irrational behaviors that cost a lot of money.

You may have heard a version of this joke:

Q. What do you call a short-term trade that doesn’t work out?

A. A long-term investment.

Here’s how that works:

Bob believes a certain stock will have strong earnings and a string of profitable quarters ahead. He buys the stock, assuming the earnings report will be a catalyst for a nice move higher.

Alas — the earnings report is bad. The company failed to meet expectations. The outlook is “meh” and was supposed to be great. The stock goes in the wrong direction. It gaps down and starts drifting lower.

At this point, Bob experiences the cognitive bias known as “loss aversion.” His desire to avoid a loss is stronger than his desire to seek gains. So, he holds onto the losing position.

If he waits a little while, Bob reasons, then maybe the stock will come back. Never mind that his whole thesis for buying the stock in the first place (strong earnings and rising profits) has been trashed.

Now that Bob’s short-term trade is a “long-term investment,” he has a vested interest in seeing the stock go up. This translates to an emotional desire — Bob deeply wants the stock to make a comeback.

Confirmation bias then takes hold: Bob’s brain starts paying attention to articles that are friendly to the idea the stock might come back … while discounting or ignoring evidence that the stock could go lower.

There is so much written about publicly traded stocks, it’s almost always possible to find a bullish article or someone making a weak bullish case somewhere — even if the stock is a total dog. Caught in the grip of confirmation bias, Bob seeks out these bullish articles. The stock keeps falling.

Bob ignores the strongly negative evidence — the warning signs in front of his nose — and stays with the position. A year later, the stock has fallen dramatically … and badly damaged Bob’s portfolio.

This can happen to anyone. It even happens to hedge fund billionaires.

The tricky thing about cognitive bias is that, much of the time, you don’t even know it’s there. The bias factors play out in the realm of the subconscious.

At no point did Bob (our hypothetical investor) realize that he was acting irrationally as the stock kept going down. In the real world, Bill Ackman (a billionaire) did the same with Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

But cognitive biases can be trickier still — because they still distort things even when you spot them.

When a bias is strong enough, it creates a form of “cognitive illusion.” This causes you to see something that isn’t there, or to wrongly perceive an irrational course of action as rational. And even if you recognize what’s happening, the illusion persists.

We can use a visual cognitive illusion to demonstrate the point.

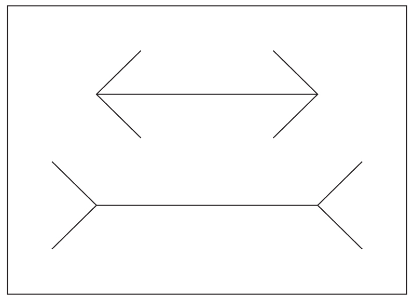

The “Müller-Lyer Illusion” was developed in 1889 by Franz Carl Müller-Lyer, a German sociologist. A version of it from Daniel Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow, appears below.

As you look at the illusion, ask yourself: Which of the two horizontal lines is longer?

The correct answer is: It’s a trick question. Both of the horizontal lines are exactly the same length. (You could prove this by taking a measurement.)

The illusion persists even after you know the correct answer. The bottom line still looks longer, even when you know the truth. This is due to a quirk of how the brain works and how certain shapes are interpreted relative to depth perception.

Certain types of cognitive bias can create a similar type of illusion. But these illusions are patterns of thought or beliefs rather than visual brain teasers. That makes them far more dangerous.

In the world of investing, persistent cognitive illusions (created by built-in cognitive biases) can lead to irrational decision making, which winds up costing investors money. Sometimes a LOT of money.

And the real challenge is, you can study up on the various biases … and be fully aware that you have them (just like everyone else) … and still fall victim to them anyway.

This is another benefit of using a set of rules that exists outside your

brain … while interpreting market data with the help of software that informs and guides decision making.

A well-designed software algorithm doesn’t see with human eyes. Technically speaking, it doesn’t “see” at all. It just crunches a vast stream of ones and zeroes. That helps make the algorithm a reliable interpreter — an impartial judge, if you will — when programmed correctly.

And this, again, is why software can be such a help to investors.

You won’t always know when your cognitive biases (which all investors share) are negatively impacting your investing decisions. And sometimes those biases will distort your perception … even if you are well aware of them and know they exist.

But well-designed investment software can help you see “in front of your nose” in terms of making rational decisions with the help of data — thus increasing the likelihood of investment success.